March 3

St. Katherine Drexel

“It is a lesson we all need—to let alone the things that do not concern us. He has other ways for others to follow Him; all do not go by the same path. It is for each of us to learn the path by which He requires us to follow Him, and to follow Him in that path.”

St. Katherine Drexel

Katherine Drexel was born in Philadelphia in 1858, the daughter of a very rich banker and philanthropist. Although she lost her birth mother only weeks after she was born, her father remarried; and Katherine’s step mother was a devout Catholic, devoted to serving the poor. Katherine grew up in a household in which both parents viewed wealth as something to be used to benefit others. When her parents died in 1885, both Katherine and her sisters became heirs to an enormous fortune. Their early upbringing showed forth, however, and they began sharing the income from her family’s estate.

Always interested in the condition of Native Americans, she obtained an audience with with Pope Leo XIII to plead for that charitable cause. The pope challenged her, saying, “Why not, my child, yourself become a missionary?” Returning home, she left on a tour of the American West, and was greatly affected by what she saw. In 1891 she founded a religious order, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, that combined prayer with social action.

During her lifetime she gave away about twenty million dollars, none of which went to her order. Relying on their own devices, her order established 145 Catholic missions and twelve schools for Native Americans, and fifty schools for blacks, Xavier University in New Orleans, Louisiana, the first United States university for blacks. In 1935 she suffered a major heart attack, retired, and spent the next 18 years in a life of prayer and contemplation. She died in 1955 and was canonized 45 years later by Pope St. John Paul II, the first natural-born U.S. citizen saint.

March 7

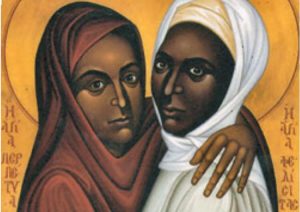

Sts Perpetua and Felicity

Perpetua and Felicity were Christian martyrs of the 3rd century. Vibia Perpetua was a recently married well-educated noblewoman, said to have been 22 years old at the time of her death, and mother of an infant she was nursing. Felicity, a slave imprisoned with her and pregnant at the time, was martyred with Perpetua.

The two women were persecuted for their Christian beliefs in Roman-owned Carthage. Perpetua documented their tortures, and her writings are the earliest surviving text written by a Christian woman.

When they were tried, Felicity was exempted from the death penalty because she was pregnant. Two days before they were to be put to death, though, she gave birth, allowing her to be martyred with her friends and loved ones.

On the day of their execution, the women were first whipped and then led into an amphitheater, where they were to be torn to pieces by a wild cow. The animal brutalized them, but they were not killed. They were then to be put to death by the blade of a sword. Felicity’s execution went smoothly, but Perpetua’s executioner’s hand slipped and pierced between her bones, failing to kill her. Perpetua then grabbed the man’s hand and guided the sword to her own neck. It was later said that she was so great a woman she could not be slain unless she herself willed it.

“Stand fast in the faith, and love one another, all of you, and be not offended at my sufferings.”

Last words of Saint Perpetua

March 9

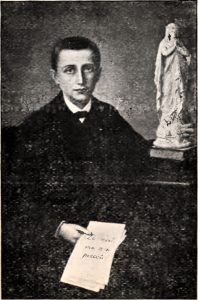

St. Dominic Savio

The son of a blacksmith and seamstress, Dominic was born in San Govanni di Riva in Piedmont, Italy. From the age of seven, Dominic desired to become a priest. Although he was young, Dominic was clearly different than his peers. When two boys stuffed a school heating stove with snow and rubbish. The boys were known troublemakers and were likely to face expulsion if caught, so they blamed Dominic for the misdeed. Dominic did not deny the accusation and he was scolded before the class. However, a day later the teacher learned the truth. He asked Dominic why he did not defend himself while being scolded for something he did not do. Dominic mentioned he was imitating Jesus who remained silent when unjustly accused.

At twelve he met Saint John Bosco, who accepted him into his Oratory, an educational center for boys in Turin. Dominic’s goal was to work with neglected and disadvantaged children when he became a priest. John guided Dominic’s youthful enthusiasm, teaching him to turn away from extreme penances and toward prayer and joyful play.

Dominic’s approach was simple. “I can’t do big things,” he said, “but I want all I do, even the smallest thing, to be for the greater glory of God.” He was well-liked, known to all as a peacemaker and an organizer. When once two classmates were on the verge of a violent fight, he rushed into their midst holding a crucifix aloft: “Before you fight, look at this, both of you.” In the face of the earnest Dominic and their suffering Savior, the boys backed down. Dominic was accustomed to what he called “fits,” moments of ecstatic prayer.

He helped to found a group he called the Company of the Immaculate Conception. All of its members except one would join John Bosco in that saint’s Salesian order. The exception was Dominic. When he fell ill at the age of fifteen with a lung disease that continually grew worse, he was sent home to his parents. Just before he died, he received a final vision. “I am seeing the most wonderful things,” he told his father.

His birthplace is now a retreat house for teenagers; he is buried in the basilica of Mary, Help of Christians in Turin, not far from the tomb of his mentor, teacher and biographer, Saint John Bosco.

“Nothing seems tiresome or painful when you are working for a Master who pays well; who rewards even a cup of cold water given for love of Him.”

St. Dominic Savio

March 12

Bl. Rutilio Grande

Rutilio Grande (1928–1977) was born in the small town of El Paisnal on July 5, 1928. He was the youngest of seven children of Salvador Grande and Cristina García. When his parents separated, his father went to look for work on a banana plantation in Honduras, leaving him to be raised by his mother and, later, his grandmother Francesca. Francisca was a very religious woman, a “prayer leader” (rezadora), in common parlance. Rutilio gave her credit for setting the foundations of his priestly vocation.

When he was 12 years old, Rutilio wrote to Archbishop Luis Chávez about his desire to be a priest. The archbishop prioritized encouraging vocations among the poor, and subsequently invited Rutilio to enter the minor seminary of San Salvador in 1941. He discerned a vocation with the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and pronounced his vows as a religious in 1947. He celebrated his first Mass on the feast of Saint Ignatius in 1964.

Rutilio’s preference for the poor was reflected in his development of several generations of seminarians, into whom he instilled a strong sense of service. When sisters and priests like Rutilio Grande took the side of the poor, the backlash from the military and oligarchy was intense. Death squads commissioned by the military and wealthy Salvadorans tortured and executed campesinos who took an active role in organizing. Their bodies would be buried in shallow graves or dumped in public places in order to terrify others into silence. The unspoken ban against killing priests was broken on March 12, 1977 when he and two companions were gunned down near his home village of El Paisnal.

Pope Francis told a friend of Rutilio Grande that the great miracle of his life was that of his old friend Oscar Romero. The Archbishop, prior to this, had been murdered avoided politics, but rushed to the countryside where Rutilio had been murdered when he learned of the assassination. The next day, Romero removed himself from all government events, and began preaching against the government’s involvement in the oppression of the campesinos. Three years later, Archbishop Romero was murdered while celebrating Mass. The twelve-year conflict eventually left 75,000 civilians dead, and 8,000 more were “disappeared”.

“If Jesus were to come to our country today, entering through Chalatenango and heading to San Salvador, he would not even get to Guazapa before being arrested for subversion and submitted to harsh treatment.”

Bl. Rutilio Grande

March 15

St. Louise de Marillac

“When all the poor in the world are no longer poor, when all the hungry are fed, and all the naked clothed, when the sick and the dying and the abandoned babies and the orphans and the outcast and the lonely and forsaken are all gathered in heaven, until that day, there will always be Daughters of Charity.”

St. Louise de Marillac

Louise de Marillac (1591-1660), wife, mother, widow, and grandmother, and leader in charity, overcame the social stigma of her birth out-of-wedlock in seventeenth-century France to became a cofounder of the Daughters of Charity (1633), an active Lady of Charity, and the patron of Christian Social Workers (1960).

As a married woman, Louise visited sick persons who were poor within her parish bringing them broths and remedies, changing their bed linen, counseling them, and burying them after their death. As a wife and mother, Louise continued ministering to the least of her sisters and brothers by bringing them food, sweets, preserves, and biscuits, and by brushing their hair, bathing their wounds, and preparing them for burial after death. As a widow, Louise was active with the Ladies of Charity by serving patients who were poor at the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in Paris, and training volunteers to do home nursing as she supervised the Confraternities of Charity, which included social ministry outreach projects initiated by Vincent de Paul. As a grandmother, Louise was conscious of teaching the lessons of charity to her little namesake, Renée-Louise.

As a leader in charity, Louise became a pioneer social worker in nursing and social services for abandoned babies, orphans, prisoners, persons living in poverty whom society disregarded because of age, frailty, mental condition, or other disabilities. Louise de Marillac was especially concerned about caring for abandoned infants, providing for orphans, and educating young girls, especially in those in the countryside.

Overcoming social barriers through a life marked by the cross from birth, Louise changed history when her work of charity and justice among the poor led her to recognize God’s presence in their midst. “How true it is that souls who seek God will find Him everywhere but especially in persons who are poor.”

The life and ministries of Louise de Marillac brought new life and hope to others. Her mission of serving God by serving the neighbor in need was rooted in respect for life and the human dignity of each person. “We owe respect and honor to everyone: the poor because they are the members of Jesus Christ and our masters, the rich, so that they will provide us with the means to do good for the poor.”

March 19

St. Joseph, Spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary

We know little of the life of St. Joseph; only what is preserved in Scripture. The 13 New Testament books written by Paul (the epistles) make no reference to him at all, nor does the Gospel of Mark. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the Apocryphal Date for Joseph’s birth is 90 BC in Bethlehem. In art, Joseph is often portrayed as an older man, with grey hair and a beard, often balding.

The Gospels describe Joseph as a “tekton,” which traditionally has meant “carpenter,” and it is assumed that Joseph taught his craft to Jesus in Nazareth. We know he was poor, for when he took Jesus to the Temple to be circumcised and Mary to be purified he offered the sacrifice of two turtledoves or a pair of pigeons, allowed only for those who could not afford a lamb (Luke 2:24).

Despite his humble work and means, Joseph came from a royal lineage. Both Luke and Matthew mark his descent from David, the greatest king of Israel (Matthew 1:1-16 and Luke 3:23-38). Indeed the angel who first tells Joseph about Jesus greets him as “son of David,” a royal title used also for Jesus.

We know Joseph was a compassionate, caring man. When he discovered Mary was pregnant after they had been betrothed, he knew the child was not his but was as yet unaware that she was carrying the Son of God. He knew women accused of adultery could be stoned to death, so he resolved to send her away quietly to not expose her to shame or cruelty. However, when an angel came to Joseph in a dream and told him that she miraculously carried the Messiah, he did as the angel told him and took Mary as his wife. (Matthew 1:19-25).

When the angel came again to tell him that his family was in danger, he immediately left everything he owned, all his family and friends, and fled to a strange country with his young wife and the baby; thus, he is a patron saint of immigrants. He waited in Egypt without question until the angel told him it was safe to go back (Matthew 2:13-23).

We know Joseph respected God. The Bible describes St. Joseph as a “just” man. In the Bible, this refers to someone who is not just “fair”, but one who is completely and joyfully a willing participant in God’s plans. When God called, Joseph responded, whether it was to flee to Egypt or to accept his betrothed Mary, despite her apparent circumstances. He followed God’s commands in handling the situation with Mary and going to Jerusalem to have Jesus circumcised and Mary purified after Jesus’ birth. We are told that he took his family to Jerusalem every year for Passover, something that could not have been easy for a working man.

We know Joseph loved Jesus. His one concern was for the safety of this child entrusted to him. Not only did he leave his home to protect Jesus, but upon his return settled in the obscure town of Nazareth out of fear for his life. When Jesus stayed in the Temple we are told Joseph (along with Mary) searched with great anxiety for three days for him (Luke 2:48). We also know that Joseph treated Jesus as his own son for over and over the people of Nazareth say of Jesus, “Is this not the son of Joseph?” (Luke 4:22)

Since Joseph does not appear in Jesus’ public life, at his death, or resurrection, many historians believe Joseph probably had died before Jesus entered public ministry. The Apocryphal Date of his death is July 20, AD 18 in Nazareth. He is the patron saint of the dying because, assuming he died before Jesus’ public life, he died with Jesus and Mary close to him, the way we all would like to leave this earth.

To give life to someone is the greatest of all gifts. To save a life is the next. Who gave life to Jesus? It was Mary. Who saved his life? It was Joseph. Be silent, patriarchs, be silent, prophets, be silent, apostles, confessors and martyrs. Let St. Joseph speak, for this honor is his alone; he alone is the savior of his Savior.

Blessed William Joseph Chaminade

March 23

St. Rafqa Pietra Choboq Ar-Rayes

St. Rafqa is a patron of those who have lost parents and against bodily ills and sickness.

“I am not afraid of death which I have waited for a long time.

St. Rafqa

God will let me live through my death.”

Rafqa (Rebecca) was the only child born to a poor village couple in Himlaya, Lebanon in 1832. She had a relatively happy childhood until her mother died when she was seven; her father’s financial troubles meant that she had to work as a servant for several years. When her father found a new wife, though, Rafqa felt the pressure to marry. She left home secretly and fled to the convent of the Mariamette sisters, a teaching order. At first assigned to work in the kitchen, Rafqa also learned Arabic, writing, and mathematics, and taught school children.

When Rafqa was forty, a crisis within the Mariamette Order led her to transfer to a monastery of the Lebanese Maronite Order. The change to a contemplative life suited her. Yet she wanted to give Christ more: in prayer, she begged for a share in his suffering. Almost immediately, she was struck with severe pain in her eye.

A botched surgery to correct the problem created an issue with her other eye, and eventually she became totally blind. For the last seventeen years of her life, Rafqa lost the use of her legs. From this time, her chief work was knitting socks by hand. She barely ate, telling others that she was satisfied by the daily Eucharist, which tasted to her of honey.

Rafqa died at the age of eighty-one, four minutes after receiving final absolution. After her burial a light appeared on her grave for 3 nights and the smell of violets emanated from it. She is called “The Flower of Lebanon.” Over 2,600 reported favors have been granted to those who touch the soil from her grave. Beginning four days after her death, miraculous cures were recorded at Rafka’s grave, the first being Mother Doumit whose throat was slowly closing so there was fear she would starve to death. Elizabeth En-Nakhel from Tourza, northern Lebanon, was cured from uterine cancer, through Rafqa, in 1938, the miracle which permitted her beatification.

March 24

St. Oscar Romero

A church that doesn’t provoke any crises, a gospel that doesn’t unsettle, a word of God that doesn’t get under anyone’s skin, a word of God that doesn’t touch the real sin of the society in which it is being proclaimed — what gospel is that?

St. Oscar Romero

Oscar Romero was born to a large family in El Salvador in 1917. He studied carpentry before entering the minor seminary at fourteen. After his studies were completed, he was ordained a priest in Rome in 1942. He returned to his homeland, where for over twenty years he served as a pastor in San Miguel, El Salvador. When he was named Bishop of Santiago de Maria, his efforts to serve his flock brought him before the conflict between the peasants, many of whom lived in crushing poverty, and the wealthy landowners, who sought to retain their control with the help of the military. He was considered to be a religious and social conservative when he was appointed.

In 1977, Romero was named Archbishop of the capital, San Salvador. The government welcomed his appointment, but ten days later, one of his friends Fr. Rutilio Grande, who had been living among impoverished farmers, was assassinated by a death squad. Romero was deeply affected. From this time, Oscar’s radio sermons increasingly addressed the inequality of a system that held so many in poverty and the immorality of the use of force against the innocent. When an ultra-right wing government seized power in 1979, Romero became an outspoken critic of the regime’s violations of human rights and outright terrorism, including unofficial government death squads.

On March 23, 1980, he made an eloquent radio plea urging those of his flock who were serving in the military to refrain from killing unarmed civilians. called on the Salvadoran military to cease its oppression. “Brothers, you belong to our own people. You kill your own brother peasants; and in the face of an order to kill that is given by a man, the law of God that says ‘Do not kill!’ should prevail.” His pleas effectively became his death warrant.

The next day, while he was saying Mass in a hospital chapel, he was shot dead by an assassin.

In his 2018 canonization Mass for Oscar, Pope Francis praised him as one who “left the security of the world, even his own safety, in order to give his life according to the Gospel— close to the poor and to his people.”

March 29

St. Berthold of Mount Carmel

St. Berthold was born in Limoges, France, the son of a Count. He excelled at his studies at the University of Paris and was ordained a priest. Berthold joined his brother, Aymeric, the Latin patriarch of Antioch, in Turkey. The two joined together to participate in a Crusade to the Holy Land. He was in Antioch during its siege by Saracens.

Following a vision of Christ, Berthold gave up the military life and joined a group of hermits on Mt. Carmel, and established a rule for their community. Many hermits scattered throughout Palestine gravitated to St. Berthold and his new community. Aymeric appointed Berthold the superior of the new community, which he headed for the next 45 years, until his death in 1195.

Following his death, the community became known as the Hermit Brothers of St Mary of Mount Carmel. It was the life and work of Bl Berthold that laid the foundation for the Carmelite Order, which, in 1206 received a written rule from St Albert of Jerusalem, whose rule was approved by Pope Honorius III in 1226. After a long absence, the Carmelites returned to their original home on Mt. Carmel in 1631, building the Stella Maris Monastery in the 18th century.